Geo-Blocking ban to unlock e-commerce: what are the main changes for traders and how Netflix has managed to escape

When it comes to Internet and digital technologies, we obviously know they are radically transforming almost every area of trade. However, some of the existing barriers in the field of online exchanges imply that EU citizens cannot exploit all the possibilities related to goods and services, that online businesses and start-ups see their horizons of maneuver reduced and that companies and governments cannot benefit fully of digital tools. In the last few years, European institutions have finally decided that it was time to adapt the EU’s single market to the digital age, breaking down regulatory barriers and moving from the current 28 national markets to a single market[1].

In November 2014, when Jean-Claude Juncker took over as president of the European Commission, executive arm of the Union, he made a unified digital continent the priority of his mandate, hoping to stimulate a process of growth that, according to an analysis prepared by the European Parliament, could bring 415 billion euros a year to the Old World’s economy and create hundreds of thousands of new jobs.

More quickly than expected, the commission managed to deliver, at least on paper, by publishing its “Digital Single Market Strategy”, on 6th May 2015[2], with the purpose to establish common rules for online purchases, integrate telecoms regulations, push postal services to offer better and cheaper parcel delivery across EU borders and reduce the burden on businesses caused by varying VAT regimes.

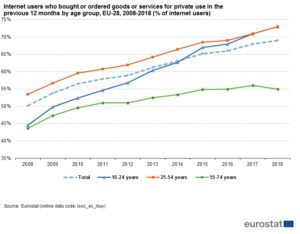

Surveys have shown that consumers[3] and businesses, especially small and medium-sized ones, are increasingly interested in buying across the EU. According to Commission figures, in 2017, 68% of Internet users in the EU have made online purchases while, in 2018, 36% of e-buyers made purchases from sellers in other EU countries, compared with 26% in 2013[4].

However, professionals often still refuse to sell to customers from another Member State, or to supply them, for no objective reason, or to offer them prices as favourable as those offered to local customers. According to a survey conducted by the European Commission, only 37% of websites allow customers of another Member State to arrive at the final stage preceding the confirmation of the order and, during 2016, in no less than 26% of cases there was a payment problem despite the common currency.

The Commission regularly receives complaints regarding customer discrimination cases for grounds related to their nationality, place of residence or place of establishment. This issue concerns both consumers and businesses that buy goods and services for their own needs, and affects both the digital and physical contexts.

Agree to disagree, the Commission has undertaken a number of important efforts to make the Digital Single Market a reality. These include the abolition of roaming surcharges[5] and the portability of digital content – enabling people to access their legally bought music, movies, TV series, e-books, audiobooks, etc. also when travelling to another EU Member State as well as the GDPR’s entry into force on 25th May 2018[6] with the aim to help harmonise rules for all players, which represents the biggest overhaul of online privacy since the birth of the internet (and the groundwork for a model to follow[7]).

It is within this frame that EU progressively prepared itself to get a clean shot against “Unjustified Geo-Blocking, a certain practice of traders who, while operating in one Member State, manage to block or limit access to their online interfaces, such as websites and apps, by customers from other Member States wishing to engage in cross-border transactions.

This misbehaviour has been identified by the European institutions as a cumbersome obstacle to the project of a unique and free digital market across all Europe. Such “geographic discrimination” may also occur when a customer intends to purchase goods and services “offline” – for instance when consumers are physically present where the professionals carry out the sale, but are prevented from accessing a product or a service, or different conditions of purchase are imposed, for reasons of nationality or residence.

By adopting Regulation (EU) n. 2018/302[8], European Union intends to offer more opportunities to consumers and businesses in its internal market, establishing directly applicable provisions which intend to prevent the occurrence of such practices in certain situations where there is no objective justification for the use of different treatment. It applies to all professionals who offer their goods and services a EU consumers, whether or not they are established in the EU and, consequently, professionals established in non-EU countries but operating in the EU are subject to the regulation.

Focusing on the main features of the new legislation, we notice that the latter defines some cases in which geographical blocks or other forms of different treatments among consumers are not duly justified.

These specific situations are the sale of goods without physical delivery, the sale of electronically supplied services, the sale of services provided in a specific physical location. For the sake of simplicity, European Commission, in its press release dated November 20, 2017 (http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-17-4781_en.htm), also set out three examples of how the ban will operate to assist consumers wishing to buy products or obtain services from different member states:

- A Belgian customer wishes to buy a refrigerator and finds the best deal on a German website. The customer will be entitled to order the product and collect it at the trader’s premises or organise delivery himself to his home.

- A Bulgarian consumer wishes to buy hosting services for her website from a Spanish company. She will now have access to the service, can register and buy this service without having to pay additional fees compared to a Spanish consumer.

- An Italian family can buy a trip directly to an amusement park in France without being redirected to an Italian website.

More specifically, concerning the free access to websites, Article 3 of the regulation prohibits blocking access to websites and redirecting the customer to other sites without your prior consent; this allows customers to access different sites national web sites and increases price transparency.

This provision also applies to non-audiovisual services provided electronically, such as e-books, music, videogames and software. If you are wondering what this would mean in practice, think about the example of an Irish customer who wants to access the Italian version of a clothing store’s website. While typing the URL of the Italian site, he or she would have been automatically redirected to the Irish site. After December 3, 2018, redirection to another site requires the explicit consent of the customer. Moreover, even if the customer should express your consent to redirection, the version of the site you intended to visit originally should remain accessible.

Besides, with reference to the access to goods and services, Article 4.1 says: “A trader shall not apply different general conditions of access to goods or services, for reasons related to a customer’s nationality, place of residence or place of establishment, where the customer seeks to:

(a) buy goods from a trader and either those goods are delivered to a location in a Member State to which the trader offers delivery in the general conditions of access or those goods are collected at a location agreed upon between the trader and the customer in a Member State in which the trader offers such an option in the general conditions of access;

(b) receive electronically supplied services from the trader, other than services the main feature of which is the provision of access to and use of copyright protected works or other protected subject matter, including the selling of copyright protected works or protected subject matter in an intangible form;

(c) receive services from a trader, other than electronically supplied services, in a physical location within the territory of a Member State where the trader operates.”

Here’s where the problems begin. Indeed, while the Regulation does not create an obligation on traders to sell, it does prohibit traders from discriminating on the basis of a customer’s nationality, residence or establishment when selling[9]. Therefore, traders remain, obviously, free to set different prices on websites targeting different customer groups, but they also remain free, in principle, to define the geographical area in which they provide delivery services. But since the Regulation does not introduce an obligation on traders to deliver across the EU, it seems quite difficult to imagine how, for instance, if a French company cannot deliver a washing machine to a Greek customer, the customer should plan the delivery of such product on his/her own.

Moreover, audiovisual services do not fall within the limits set by the Regulation – and that’s actually the real supermassive black hole in the new legislation – as Preamble 8 specifies that audiovisual services, including those whose main objective is to provide access to the transmission of sporting events, and which they are provided on the basis of exclusive territorial licenses, are excluded from the scope of application of the regulation, certifying such notable absence.

Needless to say, Netflix is the most glaring case: as a matter of fact, the revolutionary video streaming platform will keep on offering different content depending on the country from which you are connecting. After months of negotiations, a compromise was reached whereby the new regulation will not prevent the geographical blocking of copyrighted materials, such as video and music streaming, video games and e-books.

Nevertheless, although the copyright currently remains excluded from the scope of the new legislation[10][11], this exclusion might be of short duration: within two years from the entry into force of the regulation, the Commission must consider whether to extend the scope of application to copyrighted digital services.

Some believe, of course, that this exclusion represents a missed opportunity to show that the European Union is truly a single global market (with half a billion possible consumers). However, as suggested in the previous paragraph, the Commission declared that an evaluation on the possibility to include audiovisual contents into the framework of the Geo-blocking legislation is being carried out, also considering that a revision process is already scheduled for 2020.

European Union has undertaken the rough journey to build a common market which was the first goal that the founding countries of former European Coal and Steel Community and European Economic Community established. Nowadays, in the internet age, sharing coal and steel is no longer enough but it is essential to focus on new digital economic phenomena: e-commerce and streaming. Does Regulation 302/2018 take a fresh approach to the much-debated digital age? Not really. But, for sure, this could be a further step into a larger world.

[1]“Disconnected continent”, The EU’s digital master-plan is all right as far as it goes”, May 6, 2015, https://www.economist.com/business/2015/05/09/disconnected-continent

[2] L. Berto, “Il Digital Single Market: di cosa si tratta e a che punto siamo”, Jun. 9, 2018, https://www.iusinitinere.it/il-digital-single-market-di-cosa-si-tratta-e-che-punto-siamo-10703

[3] For the purposes of the regulation on geo-blocking, “consumer” means any natural person who acts for objects that do not fall within the scope of its commercial, industrial, craft or professional activity, while “customer” means a consumer who has citizenship or residence in a Member State or an undertaking which has its place of establishment in a Member State and which receives a service or purchases a well, or intends to do so, within the Union for the sole purpose of the end use

[5] “The EU’s new roaming rules”, Jun. 15, 2017, https://www.economist.com/the-economist-explains/2017/06/15/the-eus-new-roaming-rules

[6] S. Cedrola, “Il nuovo scenario in tema di protezione dei dati personali alla luce dell’imminente applicazione del GDPR”, Nov. 9, 2017, https://www.iusinitinere.it/nuovo-scenario-dati-personali-applicazione-gdpr-6131

[7] R. Waters, “California passes broadest digital privacy law of any US state”, Jun. 29, 2018, https://www.ft.com/content/671a7010-7b2a-11e8-bc55-50daf11b720d

[9] J. Rivas, J.C. Troussel, B. Heenan, “New EU Geo-Blocking Regulation: what businesses selling into the EU and across Member State borders need to do to comply”, April 2018, https://www.twobirds.com/en/news/articles/2018/global/new-eu-geoblocking-regulation-what-businesses-selling-into-the-eu-need-to-do-to-comply#2

[10] “A controversial new copyright law moves a step closer to approval”, Sep. 13, 2018, https://www.economist.com/business/2018/09/13/a-controversial-new-copyright-law-moves-a-step-closer-to-approval

[11] M. Khan, “What will change with the EU’s new copyright law?”, Mar. 26, 2019, https://www.ft.com/content/30e461bc-305c-11e9-8744-e7016697f225

Nato a Genova nel 1992, si laurea in Giurisprudenza nel 2017 ed è abilitato alla professione forense dal 2021. Da sempre amante di cinema, sport, musica ed attualità politico-economica, durante gli anni universitari sviluppa un forte interesse per la tecnologia e l’informatica giuridica. Ha conseguito nel 2020 il master LL.M. in Law of Internet Technology presso l’Università Luigi Bocconi, incentrato principalmente su proprietà intellettuale, protezione dei dati personali e diritto della concorrenza nel mondo digitale. Dopo un’esperienza di un anno presso lo European Patent Office, dove si è occupato principalmente di brevetti, design, intelligenza artificiale e strategie legate alla proprietà industriale, attualmente lavora nel dipartimento legale di Google Italy.