Online Platforms and Users’ Right to Freedom of Expression

Freedom of expression is a fundamental right “enshrined”, at the international level, in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (art 19) and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (art 19). Also regional treaties protect this fundamental right as evident in reading the American Convention on Human Rights (art 13), The African Charter on Human and Peoples Rights (art 9), the European Convention on Human Rights (art 10) and the Charter of Fundamental Rights of European Union (art 10).

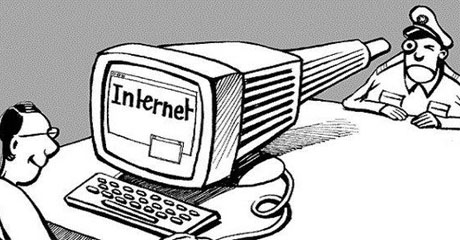

Nowadays the Internet “had now become one of the principals means of exercising the right to freedom of expression and information”[1]. In Delfi the European Court of Human Rights states that “user-generated expressive activity on the Internet provides an unprecedented platform for the exercise of freedom of expression”[2]. Furthermore in a report on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression, LaRue highlighted ‘the unique and transformative nature of the Internet not only to enable individuals to exercise their right to freedom of opinion and expression, but also a range of other human rights, and to promote the progress of society as a whole’[3].

Since their origin traditional human rights law have been designed to apply to states. However new private actors, emerged from the development of the Internet on the international scene and they are now capable of competing with the traditional powers of states in all areas, including that of human rights. In 1977, Oxford Professor Hedley Bull anticipated that in the future government authority would be shared with a variety of non-state actors, including transnational corporations, giving rise to a “neo-medieval” system[4]. Hence, similar to the existent situation, in medieval Europe the governmental functions were exercised not only by nation-states but also by private powerful actors.

In our “connected” world there is no doubt that these internet intermediaries have increasingly been playing a key role in the protection of freedom of expression. Can we state that the “duty” to protect this fundamental right of users constitutes a real legal obligation? Does international human rights regime apply to such non-state actors? Should companies be free to impose rules based on their own view of appropriate speech? Can users invoke appeal/review mechanism if in their opinion a lawful content was taken down by the platform?

In order to answer the aforementioned questions, it is essential to draw the two different approaches and degrees of protection of freedom of expression across the ocean.

Let’s first consider the US approach of freedom of expression. Following the First Amendment “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances”.

In the US framework the right of freedom of expression is absolute and doesn’t need to be balanced with other constitutional interests. This can be explained by the market place of ideas doctrine, that is, the notion that limiting speech will lead to the suppression of the truth[5].“Unless we have a direct and immediate threats or attacks to the rights of individuals, particularly in regard to their physical integrity”, freedom of expression should not be limited[6].

Those that take most of the advantages from the provision contained in the First Amendment are big media companies because that freedom applies to individuals but also to corporations or associations. This means that in the US online platforms do not have the obligation to protect users’ freedom of expression because the platform in itself owns that right. Thus, social media like Facebook and Instagram can decide in their Terms of Service what is allowed, considering their own conception of freedom of expression. The platform is a private space where the rules are imposed by their owner and users have to comply with them on the basis of their contractual relationship with the service provider. The decision of the platform in this context would be fully lawful without possibility to benefit from review/appeal mechanisms.

Therefore, in the US this debate will never go further considering this broad approach of freedom of expression.

However, in European Union there is more foods for thoughts.

Following Article 10 European Convention on Human Rights: “Everyone has the right to freedom of expression. This right shall include freedom to hold opinions and to receive and impart information and ideas without interference by public authority and regardless of frontiers”. The European perspective is well reflected in the Handyside case 1976 where we find a strict connection between freedom of expression and the idea of democratic society and pluralism. Even “information” or “ideas” considered offensive, shocking or disturbing by the State or its citizens are protected under article 10[7].

This right has, however, its limitations. Following article 10(2) European Convention on Human Rights “the exercise of these freedoms, since it carries with it duties and responsibilities, may be subject to such formalities, conditions, restrictions or penalties as are prescribed by law and are necessary in a democratic society, in the interests of national security, territorial integrity or public safety, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, for the protection of the reputation or rights of others, for preventing the disclosure of information received in confidence, or for maintaining the authority and impartiality of the judiciary”. The European Court of Human Rights has given these limitations a strict interpretation, especially when there are political speech and matters of public interest involved in[8]. A three-part test is required for any content-based restriction. Similarly, to Article 19 paragraph 3 of ICCPR the restriction or interference must be established by law, necessary and proportionate[9].

For the purpose of our research it is important to note that in EU there are new regulatory trends which directly affect the liability regime of online platforms. Within this movement there is also the belief to impose intermediary the obligation to protect freedom of expression, to make platforms function as an extension of states in order to enforce the law. Hence more and more often public and private roles are being mixed up.

This is evident considering the recent development of codes of conduct[10]and new legally binding regulations. For instance, the new Audiovisual Media Services Directive, which has been recently adopted, will impose new duties on Internet service providers concerning content regulation, in addition to the already existent responsibility to take down known unlawful content, laid down in the E-Commerce Directive[11]. Platforms must enforce these rules under the supervision of administrative authorities. Therefore, via this delegation of states platforms have the obligation to protect freedom of expression and they can limit this right only in case of contents pertaining to hate speech, child pornography, protection of minors and terrorism.

This means that if a post was taken down by a platform the applicant can ask for a review mechanism arguing the violation of his freedom of expression. In this sense we can affirm that platforms have an obligation to protect users’ freedom of expression. However, there is still a way for platforms to circumvent those obligations as their decisions can be based on Terms of Service resulting from the application of the law, where review mechanisms are available, but also on the application of their internal Terms of Service. In the latter situation it will not possible for users to challenge their decision through review mechanism, even if the reason to restrict speech is related to the maximization of platform’s revenues[12].

In conclusion the duty that platforms have to protect users’ freedom of expression may be understood as a real obligation, depending on the broadness that we give to that right and on the legal circumstances surrounding its application. The new regulatory trends that emerged in the EU framework constitute a positive start towards this end. “In our neo-medieval world, the most viable way to protect individuals’ freedoms of expression rights is to seek to have governments implement their international human rights obligations regarding speech and encourage companies to align their codes with these standards”[13]. Hence, it is only by reinforcing the state’s role as gatekeeper that we can preserve our fundamental rights on the Internet.

[1]ECtHR, Ahmet Yildirim v Turkey, 18 December, 2012; See also S. Cedrola, “ Social media, libertà d’espressione e attività legislativa: un complicato bilanciamento di interessi”, July 2018, available at: https://www.iusinitinere.it/social-media-liberta-despressione-e-un-complicato-bilanciamento-di-interessi-11870;See alsoA. Rovesti “Il riconoscimento della libertà di manifestazione del pensiero negli ordinamenti statali occidentali e nel diritto internazionale”, September 2017, available at: https://www.iusinitinere.it/riconoscimento-della-liberta-manifestazione-del-pensiero-negli-ordinamenti-statali-occidentali-nel-diritto-internazionale-4595

[2]ECtHR, Delfi AS v Estonia, 16 June, 2015

[3]Report of the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression, Frank La Rue, A/HRC/17/27, 16 May 2011

[4]HEDLEY BULL, THE ANARCHICAL SOCIETY: A STUDY OF ORDER IN WORLD POLITICS 245–46, 254–266 (2d. ed. 1995). See also ANTHONY CLARK AREND, LEGAL RULES AND INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY 180–84 (1999)

[5]Andrew Murray, Information Technology Law: The Law and Society (2nd edn, Oxford University Press 2013)

[6]Annabel Hili, THE BOUNDARIES OF FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION ON SOCIAL MEDIA: REGULATING INCITEMENT TO COMMIT CRIMES AND HATE SPEECH IN AN ONLINE ENVIRONMENT, June 2015

[7] Ibidem; ECtHR, Handyside v. United Kingdom, 7 December 1976

[8]ECtHR, Willem v France, 16 July 2009

[9]See communication no 1022/2001 Velichkin v. Belarus, Views adopted on 20 October 2005

[10]See Code of Conduct on Countering Illegal hate Speech Online (2016)

[11]Joan Barata, The new audiovisual media services directive: turning video hosting platforms into private media regulatory bodies, 24 October, 2018 available at: directive-turning-video-hosting-platforms-private-media

[12]Joan Barata, New EU rules on video-sharing platforms: will they really work?, 18 February, 2019 available at: http://cyberlaw.stanford.edu/blog/2019/02/new-eu-rules-video-sharing-platforms-will-they-really-work

[13]Aswad, Evelyn, The Future of Freedom of Expression Online (August 15, 2018). 17 Duke Law & Technology Review 26 (2018), available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3250950

Image source: thephilanews.com

Laureata in Giurisprudenza presso l’Université Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne, con specializzazione in diritto pubblico, con il massimo dei voti. Dopo aver integrato la sua formazione, come Visiting Student, presso l’Università di Cambridge e l’Università della California Los Angeles (UCLA), continua i suoi studi presso l’Université Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne, conseguendo un Master di primo livello in Diritto Internazionale.

Particolarmente interessata all’applicazione del diritto nell’era digitale, si candida ed è ammessa all’edizione 2018-2019 del LL.M in Law of Internet Technology, presso l’Università Commerciale Luigi Bocconi di Milano.

La sua formazione le permette di avere una conoscenza livello madrelingua della lingua francese e inglese, oltre ad una buona padronanza della lingua spagnola.